Hepatitis B—A Silent Killer

“I was 27 years old, recently married, and I looked and felt healthy. I was holding down a high-pressure job while caring for many responsibilities in the local environment where I serve God. I was unaware that hepatitis B had begun to destroy my liver.”—Dukk Yun.

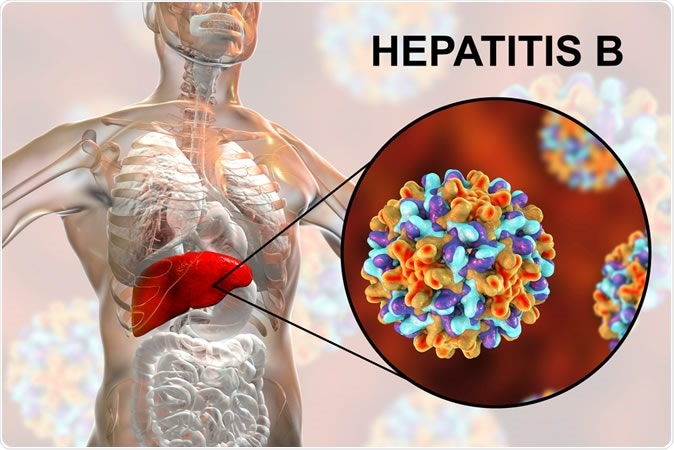

THE liver filters poisons from the blood and performs at least 500 other important functions. That is why hepatitis—inflammation of the liver—can devastate a person’s health. Hepatitis may result from excessive alcohol consumption or exposure to toxins. Most often, though, viruses are the culprit. Scientists have identified five such viruses and believe that there are at least three more.

Just one of the five—hepatitis B virus (HBV)—kills at least 600,000 people a year, comparable to the toll taken by malaria. More than two billion people—nearly a third of the world’s population—have been infected with HBV, and most recovered within months. For about 350 million, however, the disease became chronic. For the rest of their lives, whether they have symptoms or not, they will have the potential to infect others.

Proper medical care, started early, can help some with chronic HBV to ward off serious liver damage. But most are unaware that they have been infected, as only a specific blood test can detect HBV. Even routine liver function tests may come back normal. Thus, HBV can be a silent killer, striking without warning. Obvious symptoms may not appear until decades after infection. By then, either cirrhosis or cancer of the liver may have developed. These diseases take the life of 1 in 4 HBV carriers.

“How Did I Get HBV?”

“My symptoms first occurred at age 30,” says Dukk Yun. “I had diarrhea, so I went to a doctor of Western medicine, but he treated only the symptoms. I then saw a traditional Asian doctor, who gave me medicine for my intestines and stomach. Neither doctor checked for hepatitis. Because the diarrhea persisted, I returned to the Western doctor. He gently tapped the right side of my abdomen, which caused me pain. A blood test confirmed his suspicion—I was carrying the hepatitis B virus. I was shocked! I had never had a blood transfusion, nor had I been sexually promiscuous.”

After Dukk Yun learned that he had HBV, his wife, parents, and siblings had their blood tested, and all had antibodies to HBV. In their case, however, their immune systems had cleared the virus from their bodies. Had Dukk Yun acquired HBV from one of them? Had they all been exposed to a common source? No one can be sure. Indeed, in about 35 percent of cases, the cause remains a mystery. What is known, though, is that hepatitis B is not hereditary and is virtually never acquired through casual contact or the sharing of food. Rather, HBV is spread when blood or other body fluids, such as semen, vaginal secretions, or saliva from an infected person, enter another`s bloodstream through broken skin or mucous membranes.

Transfusions of contaminated blood continue to infect many, especially in countries where screening for HBV is limited or nonexistent. HBV is 100 times more infectious than HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Even a tiny amount of infected blood, such as may be found on a razor, can pass on HBV, and a dried bloodstain can remain infectious for a week or more.

The Need for Understanding

“When my company learned I had HBV, they put me in a small office away from most of my colleagues,” recalls Dukk Yun. Such treatment is not uncommon and may spring from a misunderstanding of how the virus spreads. Even otherwise well-informed people may confuse hepatitis B with hepatitis A, which is highly contagious but less life-threatening. Further, since HBV can be transmitted sexually, even morally upright sufferers are sometimes viewed with suspicion.

Misunderstandings and suspicion can create serious problems. For example, in many places, people needlessly ostracize HBV carriers, young and old. Neighbors do not allow their children to play with them, schools do not admit them, and employers avoid hiring them. Fear of discrimination, in turn, keeps people from getting tested for HBV or revealing that they have the disease. Some even risk their future health and that of family members rather than disclose the truth. Thus, the deadly cycle of the disease can continue for generations.

The Need for Rest

“Although my doctor prescribed complete rest, after two months I returned to work,” relates Dukk Yun. “Blood tests and CT scans showed no sign of cirrhosis, so I thought I was fine.” Three years later, his company transferred Dukk Yun to a big city, where his life became more stressful. With bills to pay and a family to support, he kept working.

Within months, the virus count in Dukk Yun’s blood shot up and he began to feel exhausted. “I had to quit my job,” he said, “and I now regret that I worked so hard. If I had slowed down sooner, I might not have become so sick, further damaging my liver.” Dukk Yun learned a vital lesson. From then on, he cut back on his work and his expenses. Moreover, his whole family cooperated, his wife even taking on a small job to help make ends meet.

Living With Hepatitis B

Dukk Yun’s health stabilized, but his liver increasingly resisted the blood flowing through it, elevating his blood pressure. After 11 years, a vein in his esophagus burst and blood gushed from his throat, sending him to the hospital for a week. Four years later, he experienced mental confusion. Ammonia had built up in his brain because his liver could no longer filter it all out. Medical treatment, however, corrected the problem in a few days.

Dukk Yun is now 54. If his condition worsens, his options are limited. Antiviral treatments cannot clear the virus entirely and may have serious side effects. The last option is a liver transplant, but the waiting list is longer than the donor list. “I’m a ticking time bomb,” says Dukk Yun. “But it does no good to brood about it. I still have life, a place to sleep, and a fine family. In fact, in some ways, my condition has turned out to be a blessing in disguise. I have more time to spend with my family and more time to study the Bible. This calms my fear of untimely death and helps me to look forward to life without illness.”

[Note]

The disease is considered chronic if the immune system has not eliminated the virus within six months.

Ahuruonye Okezie does not endorse any particular form of medical treatment. Blood from an infected person should be cleaned up promptly and thoroughly using protective gloves and a freshly made solution of 1 part household bleach to 10 parts water. ,